We try to interrogate the Truth of the Events unfolding in Bangladesh, and claims of the death of secularism. We ask if society is experiencing a silenced, spiritual revolution and present important reference materials to make sense of the politics of curricular change, the times of Al Ghazali and the contents of the much maligned Darse Nizami. With both secular and more than secular spaces struggling to make space for history, epistemic plurality and colonial continuity we travel through China, East London and Sylhet to demonstrate how texts and people flow and interact. We amplify excluded voices, to give new readings to Events in Bangladesh today.

Avijit Roy Murder: In the search of the Truth after the Event

When the then British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan was asked what can most easily steer a government off course, he answered “Events, dear boy. Events”. One of the truisms of the statement being, is that our subjective perception of the truth is tied to ‘Events’ that we witness in our lives.

In recent times in Bangladesh, the Avijit Roy murder, seems to have shifted the knowledge of what Bangladesh means. Avijit was the joint founder of the website Mukto Mona, and was slain in mysterious circumstances in February 2015. The Bangladesh government of the day as well the corporate media has blamed the death on shadowy Islamist terrorists. The meaning derived from the ‘Event’ being, Bangladesh is now an irrational conservative Islamic country, where secular and atheist bloggers and writers fear for their lives. Even The New York Times joined in the chorus following the murder, declaring in an op ed piece, the end of secularism in Bangladesh.

In sharp contrast, two years ago, during the Shahbag protests for the hanging of Abdul Quader Mollah. The ‘Event’ was described mainly as knowledge that Bangladesh was a secular and progressive country, where as an exception to the rule, conservative Islamic forces have been beaten back and were in full retreat. So looking at the current coverage of Bangladesh, it appears the country has gone through some kind of revolution, where there has been a dramatic shift in society, within a short period of time. Or has it?

Could it be that much of the current English and Bangla social commentary on recent developments in Bangladesh is ill informed, malicious and self censored? For example if the supposed epidemic in ‘Atheist Killings’ weren’t confusing enough, Ahmede Hussain recently confused Deoband with Aligarh, in regards to being supported by the British Empire. Systematically appalling coverage prevents the public from learning and discussing underlying issues, and frames everything in terms of a third rate Hindi soap opera, produced through the pockets of the power elite.

Rage against the Nastiks (Militant Atheists): Voices from the ‘Other’ Bangladesh

Glorified is My Lord, The Magnificent: An image of congregational prayer on the streets of Dhaka 2013. Islami Andolon Bangladesh gathered in the capital to protest corruption and nepotism as well as demand restoration of the caretaker government system for political transition and new legal protections against religious defamation

Proponents and supporters of Mukto Mona would posit their writings in terms of progress and modernity, and would see themselves as the intellectual successors to the 19th century, Calcuttan, Bengali Renaissance. Their core proposition is that religion poisons everything, that it is a belief based on feeling rather than fact, hence religion is at the root of most of the problems of Bangladesh. This seems to be the general view that seems to permeate elite discourse within the country, conscious or otherwise.

However, when searching for the Truth of the ‘Event’, we have to go beyond the knowledge and discourse generated by the power structure , in our case the Bangladeshi government, elite commentators and the corporate media. We have to listen and address the voices excluded, and observe the material being reconfigured, in order to have a complete picture of the Truth. Incorporating both sides of the binary, whilst queering that binary challenges the interests gathered around the dominant pole. From a socioeconomic perspective, both sides of the debate generally fit into social classes created by widening economic inequality, initiated in colonial times and maintained by the post colonial state.

Conservative, mainly excluded voices in Bangladesh, would place the writings of Mukto Mona and its supporters within the binary of the ‘Astik vs Nastik’ debate, or militant atheist vs people of faith debate. In a background of increasing political turmoil and state security suppression, the disenfranchised conservative mood in the country manifested itself in the 2013 Hefazote protests in Dhaka. Where on two separate occasions, it is believed that over 1 million people participated in the protests. The organisers, Hefazote Islam, had a 13 point demand, the second point of the demand being:

“to stop all the anti-islamic propaganda of the self declared atheist and murtad leaders of so-called Shahbag movement and bloggers who propagate lies against the Prophet (saw) and to punish them.”

In the run up to and in the aftermath of the Dhaka massacre of May 2013, I asked Hefazote supporters as to the meaning of the 2nd point in their 13 point demand, and as to why they were so agitated by insults from atheists and former Muslim writers.

One made the issue of the difference in terms if genealogies, which leads to misunderstandings. Apostasy, in the English language, means for someone to change their minds about religion. Apostasy and apostates, using an Islamic genealogy is better translated as ‘nifaq or ‘munafiq’’. He then went onto argue, that the Prophet Muhammad (saw), knew who the apostates were and didn’t kill them. Many made the point that they were simply asking for the implementation of existing laws against hate speech.

Nearly all gave a reply that one had to distinguish between atheism and what they termed Militant Atheism. Atheism on its own is a non positive assertion, it is to believe there is no god, it is ambivalent as to whether god or religion is force for good or evil. They pointed out the Muslims in past have had a long history of coexisting with atheists, from the earliest community to the present time. For example there are the famous public debates Imam Abu Hanifah had with the atheists of his time.

‘Nastiks’ or Militant Atheists, they argued, step outside the prism of a traditional atheist, from a passive position to an aggressive one, from ‘I have no god’ to ‘you should have no god’. These ‘Nastiks’ they argued, are not equal in their hatred of religions, they are entirely fixated with Islam. As an example, they stated that this discrimination and hatred against Islam in Bangladesh is expressed explicitly, from the ban on University admissions to Madrassah students, to bans on the headscarf (hijab) in various workplaces. Implicitly it is found in reading the works of famous novelists and images in the media, in the portrayal of the characters of religious people. Such evidences are replete in Bengali dramas, novels, stories and other media and genres. An evil character is always portrayed by the image of an Islamic person, with the beard, outfits such as tupi, long dresses and lungi or pyjamas.

In conversations, social media and in their writings, proponents of such discrimination and prejudice towards observant Muslims and Islam in Bangladesh, would justify it in the name of muscular secularism. They lay out a dichotomy between a Medieval God centred Muslim culture in opposition to an Aryanising progressive world view. Thus discrimination and suppression of Muslim culture and practices is the necessary price of progress and development. Concluding, that Islam and Muslim culture in its very essence is barbaric and backwards, and its effect on society should be limited and mitigated where possible.

Black Swans: A Snapshot of the Qawmi Experience in the UK

A seminar on the Philosophy of Islamic Science and Modern Technology by Professor Datuk Osman Bakar in a Qawmi Madrassah in East London, attended by madrassah students, professionals, medics and academics. March 2015.

Looking at statistical evidence worldwide the argument that Muslims and Islam at their very essence are anti modern or development, does not hold. Many Muslim countries enjoy high per capita wealth income, some with higher than or equal to many Western countries. Even if we restrict the field to the context of Bangladesh, using the extreme example of Qawmi Madrassas both in UK and Bangladesh, the argument seems not to hold.

In recent times in Bangladesh, most of the debate around Qawmi Madrasahs, under the influence and guidance of foreign governments, is around how they are creating a large pool of graduates unable to function in a modern economy and society. Most of the arguments concluding that they need to come under state control under the guise of curriculum reform. Images of Qawmi Madrassah’s and graduates are used often in the corporate press both at home in Bangladesh and abroad to front negative articles, represented in the stories by journalists as anti progress and development forces.

Qawmi Madrassah, also known as Darul Ulooms, mainly in South Asia, are independent community run madrasahs, who are distinguished by the fact that they receive no government funding and teach one of many variations of the Darse Nizami Curriculum. The Darse Nizami curriculum is an educational syllabus which was formulated and crystallized in Lucknow, in the late Mughal period. The curriculum traces its origins and influences back into the medieval period, to Nizamuddin Awliya and Al Ghazali.

As in Bangladesh, the Qawmi Madrasahs in the UK receive no government funding, however the medium of instruction is mainly English. The difference in the UK being that madrassah students face no bar with regards to employment in public services or access to universities, hence the majority of graduates, who I encountered, go onto careers other than that of an Imam at a Mosque. A large portion go on to working in the public sector, in the NHS and Prison Services as part of the chaplaincy service, one even ended up as a chaplain for the British armed services. Many go on to universities, either through the traditional route of sitting A-Levels, entering as mature students or the unconventional route of getting the qawmi madrassah certificates accredited by the Pakistani High Commission. After graduating many have gone on to pursue careers either in Teaching, Law or Finance and Accounting. One graduate of Lalbagh Qawmi Madrassah in Dhaka, has gone on to graduate in Chemical Engineering at Imperial College London and then onto running a successful construction company.

The other phenomenon in London, when it comes to the Darse Nizami is the rise in the number of ‘Midnight Madrassas’, evening and part time classes aimed at professionals, workers and students. Here after work or study, students attend classes on religious texts. Many of whom, increasing number being women, have no intention in going onto becoming religious leaders or Imams in the mosque. This brings into question as to what is the essential function of these texts in society, past and present.

Picture of British Armed Services Chaplain, Darul Uloom graduate Asim Hafiz (OBE) 2014.

The Roles of Classical Texts in the Land of the Rising Sun

“When the Sages arose, they framed the rules of propriety (ritual) in order to teach men, and cause them, by their possession of them, to make a distinction between themselves and brutes.”

Liji – The Confucian Book of Rites

Formally the Darse Nizami, does not confer on its graduates the right to be a religious leader or Imam. What it does confer is the right to read unaided the canon of Arabic religious literature, as well as being a transmitter of the oral tradition that is at his heart. A good comparison and model of understanding, is the similarity between the roles of the Darse Nizami texts and those of the Confucian classics, in Imperial China.

Confucian texts formed the basis of the examination system of the Imperial bureaucracy in China. Thus the dissemination of the texts created a literary class in Chinese society who acted as the guardians and repository of Chinese culture from the 500 BCE upto the beginning of the 20th century. A self appointed class, whose function was to act as the guardians of Chinese civilisation and to be a bedrock of stability in times of economic and political upheaval.

“The Sage of the West, Muhammad was born after Confucius and lived in Arabia. He was so far removed in time and space from the Chinese Sages that we do not know exactly by how much. The languages they spoke are mutually unintelligible. How is it then that their ways are in full accord? The answer is that they were of one mind. Thus their Way is the same.”

Liu Zhi – Tianfang dianli

A similar observation was made by the historian and philosopher Ibn Khaldun. Ibn Khaldun in his Muqaddimah distinguished between tribalism or asabiyyah on the basis of blood and that on the basis of a shared educational experience. These networks and bonds of shared educational experience, in the Muslim world today, they can be traced through the distribution and acceptance of certain key texts. A good example is the spread of the core Darse Nizami text, the Hidayah, which was first written in the then Persian region of Greater Khorasan (the land of the rising sun). Today the Hidayah can found being taught in Europe (Bosnia and the Greek Region of Thrace), through Turkey and Central Asia, on to South Asia and even as far as Ningxia in China and Kazan in Russia. Thus it appears the texts and curriculum have a dual function not just instructing individuals in religious rites or dogma, but also creating a collective experience and memory, that supersedes the nation state, that of a shared Islamic Civilisation, the ummah.

“The Way of the Sage is none other than the Way of Heaven.”

Liu Zhi – Tianfang dianli

A Living Intellectual Tradition: In the Shadow of Shahjalal

( L) The birds at the Shahjalal Shrine in Sylhet, descendents of the original birds given to him by the Chisti Nizamuddin Auliya in Delhi ( R) Tomb of Shah Jalal in Sylhet

As in the UK, similar Black Swans to the dominant narrative of medieval Islamism versus a modernising Aryanism/Atheism can be found in Bangladesh, in this case, in Sylhet. At the heart of Sylhet city is the complex dedicated to the grave of the Sufi Shahjalal. The grave of the saint sits on top of a mound , and in its shadow at the foot of the mound, next to the main gate, within the complex is a Qawmi Madrassah, known locally as the Dargah Madrassah.

Nearly a decade ago I was visiting a friend from the UK, who enrolled on to the final year of the madrassah. During the visit, I got him to conduct a brief straw survey of his class, asking respondents about their backgrounds and motivation.

The students in the class fell broadly into three categories, corresponding to where they sat in the class (front, middle and back). Around 10% of respondents wanted to pursue a career in teaching, further learning or research. This group normally sat at the front of the class, and for sitting at the front had the privilege to read out the Prophetic traditions that were going to be studied on that day.

The second group comprising of about 60% were made up of students, who came into the madrassah for ‘welfare reasons’. The madrassah life provided them with free or subsidised lodging and food. Graduation from the madrasah, provides a route out of poverty as well as increased social status.Most wanting to opt for a quiet life of an Imam in a village or a small urban mosque.

The third group, 30% (which normally sat at the back of the class) were the most interesting. The students came from a varied background and had diverse ambitions. Many came from the state Aliyah Madrassah sector, but enrolled to access the oral tradition still preserved within the Qawmi madrassas. There were others who were products of the secular education system. For example there was an engineering student, simultaneously completing his degree while attending lectures at the madrasah. Then there was the budding journalist, drafting his articles while the traditions and commentaries were being read out in the class. All of the individuals in this group wanted to pursue a career outside the mosque or madrassa but saw madrassah education as an important companion along those career paths. When asked about the barriers that they face due to prejudice and misconception, they accepted it as a necessary price to pay for the commitment to their beliefs. They saw no contradiction between the modern society they occupy and the image of themselves as successors of a living tradition, first brought to Sylhet by Shahjalal.

Al Ghazali and the Incoherence of the Juktibadi: Then and Now

Shahjalal came to Sylhet from the then Seljuk Turk city of Konya, famous for being the resting place of Rumi. He was a product of the state sponsored education system, that was designed and pioneered by Al Ghazali nearly 200 hundred years earlier and 900 years before our time. Ghazali near the end of his life, penned his autobiography, ‘The Deliverance from Error’, where he described his intellectual and spiritual journey. On the one hand, he wrote about his encounters with religious fundamentalist, who he described as ignorant fools who do more harm than good, by rejecting science and reason in the name of defending Islam.

On the other, he wrote about the militant atheists of his day, who described themselves as free thinkers or ‘philosophers’.These free thinkers in the name of science and reason, declared Islam as a social ill towards progress and development. After various encounters and reading their works, Ghazali concluded, that despite their declarations of following reason, at the very core of their beliefs and attitudes was an irrational prejudice against religion, a domination of the ego over the intellect.

The irrational prejudice, written about by Ghazali over 900 years ago, is alive and kicking in powerful circles in Bangladesh today. This modern manifestation of the ego over the intellect has two parts. First, the argument one hears that religion is the root of most or all of the world’s problems. An irrational belief, given the last 100 years produced the mass slaughters of World War I and II, colonialism, Communism, imperialism, Korea, Vietnam and the Iraq war – all of which had nothing to do with religion.

Second, the doctrine that if one can educate and manipulate enough religious believers to ‘truth’, then the world will be perfect and all our problems will disappear. An irrational myth, following on from the Enlightenment, that physical and social environments could be transformed through scientific and rational manipulations. An irrational dogma that gave us the false utopias, of the Nazis, and Stalinism and the killing fields of Cambodia. As Chris Hedges writes, this irrational belief in, “rational and scientific manipulation of human beings to achieve a perfect world has consigned millions of hapless victims to persecution and death”.

It is not just religious Zealots that incite violence against and kill people for their beliefs. Above: Picture of victims following the state massacre of madrassah students in May Dhaka 2013.

The on going struggle (Jihad) of Liberating Theology, Past and Present

Above attempt by British Raj administrators in trying to thwart the civil disobedience campaign of Hussain Ahmed Madani.

Al Ghazali and his Seljuk patrons, saw their education policy as a prerequisite in their political programme to liberate Muslim lands in the aftermath of the European Crusades. Thus following in the footsteps of Al Ghazali, in 1857 amongst the ashes of Delhi, then burnt down by the British, the seeds of the Qawmi Madrassah movement were sown. The original pioneers saw their educational movement as an essential prerequisite to freeing South Asia from British colonial rule.

After a 150 years it seems, as opposed to many other countries around the world, that in Bangladesh, with a deteriorating human rights situation, the struggle has not finished and still continues. The Avijit Murder of 2015 occurred against a backdrop in Bangladesh, where universal franchise, in terms of free and fair elections, has been suspended and where foreign interests take precedence over domestic concerns. Thus the supposed war on terror on alleged fanatics, provides a convenient figleaf for increasing repression by the security forces against legitimate opposition activists.

These recent battle cries of the war on terror, echo earlier calls against shadowy Islamists at the time of the British Raj. Nearly a hundred years earlier, a madrassah teacher, Hussain Ahmed Madani, arrived at the Nayasorok mosque in Sylhet, to teach and instigate a non violent local movement for home rule against the British. For his activities, he and his followers were persecuted, tortured and labelled as fanatics by the Britishers. Thus it appears a century on, nothing much has changed, after two attempts at independence, things appear to have reverted back to their original state. Thus the Truth after the Event in Bangladesh is this, ‘Yes, the British have left, but they have left behind in charge, bastard offsprings with their Hindustani manservants.’

Following the Dhaka Massacre of May 2013, I had a discussion with Qawmi Madrassa teacher in the UK. He was privy to the discussions of the current and previous Bangladeshi government’s attempt at Qawmi Madrassah reform. He said all parties want reform, the madrassas want to end discrimination against their students, in terms of public sector employment and access to University education. However he added due to ideological vested interests on the Government side, negotiations have been sabotaged both in the previous BNP government and now in the current Awami League one.

He conceded that there are some vested interests within the Qawmi madrassah movement, ‘political opportunists’, who benefit from the status quo, as it gives them ownership over a ghettoised frustrated vote bank. In spite of the lack of resources and existing institutional barriers, he pointed to interesting examples of internal reforms. In the Sylhet region, following a model established in Lucknow, Arabic intensive institutions, with an accelerated Darse Nizami programme have been established. He also cited the example of a Qawmi madrasah in Comilla, which has modern IT facilities and train’s common law judges and public officials in the intricacies of Shariah Law.

As a counter example to Bangladesh, he cited pragmatically oriented reforms in Turkey, where in the 1980s barriers were removed in terms of employment and education to madrassah students (graduates of the Imam Hatip Schools). After those barriers were removed, more than a third of the students went on to graduate in Law, Finance and Business. The current President of Turkey, Recep Erdogan, being an example of an Imam Hatip school graduate choosing a mainstream career path.

When I asked him, whether the same pragmatic reasoning, as in Turkey will triumph over ‘Aryanising’ ideological hatred in Bangladesh. The Maulana answered by reciting the prayer derived from the Prophet Jacob (as):

Allahu Musta’an Sabran Jamil – Allah it is Whose Help is sought, with comely patience

Solar Eclipse Northern Europe March 2015

“Remember: oppression is temporary. Reality is light, but darkness overtook it. Islam came with a light to extinguish these tyrants, dictators and ignoramuses. Their darkness has covered us, but darkness does not last forever. This is a sign that oppression must come to an end, that this age of tyrannical rule is coming to a close, just as the light follows darkness…”

The late Naqshbandi Sheikh Nzaim Haqqani – on the Eclipse Prayer, Salaat Al Kusoof

———————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Resources and Further Reading:

- PDF Library of the entire Darse Nizami curriculum as well as other associated texts in English, Arabic and Urdu.

- Life and Times of Al Ghazali Dr T J Winter Part 1 and Part 2

- When Atheism Becomes Religion: America’s New Fundamentalists by Chris Hedges

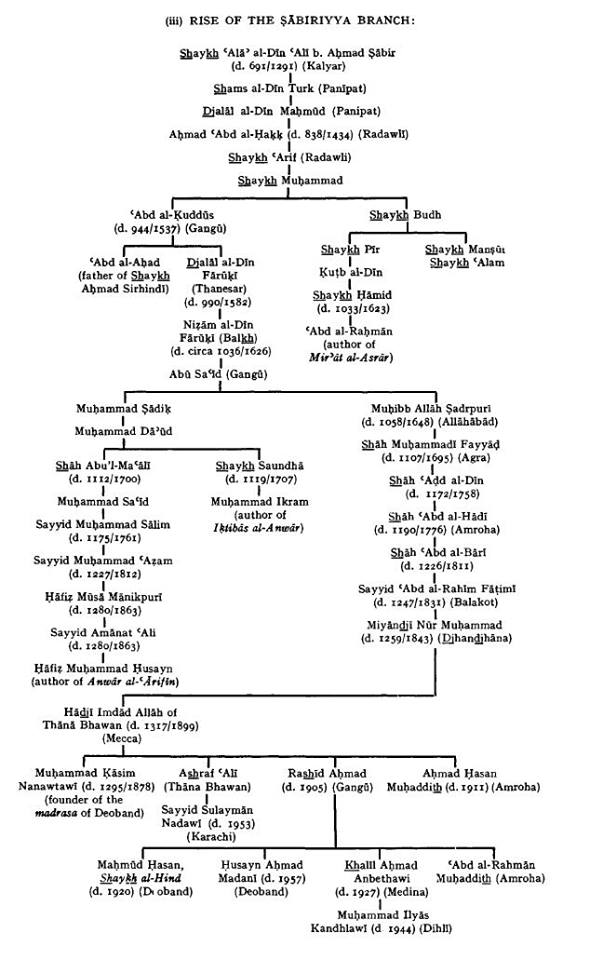

- ‘Intellectual Legacy of Shah Wali Allah’: Diagram below showing the fluid and interlinking student teacher relationships in all the varied religious movement in South Asia and the Arabian Peninsula.

- Silsilah of the Chistiyyah Sufi Tariqah: Spiritual Chain of Transmission which includes at the end, prominent political figures at the time of Independence from the British (Sulayman Nadwi and Hussain Ahmed Madani).