Jyoti Rahman

Voters of Dhaka and Chittagong are supposed to exercise their democratic right on 28 April. These elections are hardly going to change the political status quo that is Mrs Wajed’s one-person rule over Bangladesh. And yet, there is something for everyone in these elections.

In Dhaka North — where yours truly spent a part of his life — there really is a choice. Towards the end of this post, you will find the preference of this blog.

To begin with an obvious statement — these elections ended BNP’s andolon. Arguably, BNP was going nowhere in the streets. A post-mortem really deserves its own post (and I hesitate to even signal one might be in the offing). For now, there is no argument that this round went to the League.

Okay, so here is a contentious point — with these elections, the Prime Minister has given Mrs Zia an exit.

Pause, and think about this.

There is no denying that she can be brutally ruthless when she chooses to, and there must have been huge temptation to go for the opposition’s jugular. So, why did the PM hold back?

I’d argue that by holding back, and allowing her much weakened opponent a way out, the PM strengthens her hold over the establishment — the business sector, the civil-military bureaucracy, and foreign powers. Remember, the Awami-establishment bargain is based on stability. Mrs Wajed’s best and only real selling point is that she alone can provide stability. For a few weeks in January, that proposition was tested. Driving BNP underground isn’t going to do anything for stability. Allowing BNP a breathing space through local government election, on the other hand, does help with stabilisation.

Now, make no mistake that BNP is much weakened. Scores of its grass root activists (and indeed mid-level leadership) have been abducted or killed, and much of its senior leadership is in either jail or exile. Also, make no mistake that the elections are on a level playing field. But for BNP, it’s hard to see an alternative to taking the exit offered. It gives the party a chance to live for another day — there is nothing else. And even if it doesn’t fight another day, life is something.

I have no idea which way the voters will choose. It’s entirely possible that BNP will lose all three, fairly or otherwise. It’s hard to see what the ruling regime can achieve by blatant poll-day rigging (as opposed to pre-poll machinations). Plus, I am not sure BNP actually has enough strength to get-out-the-vote or maintain adequate presence in the centres on the day. That is, it is quite possible that BNP will lose a seemingly peaceful semi-decent election. Should that happen, its rank-and-file will be further demoralised, limiting the chance of another winter flair-up.

But it is also entirely possible that BNP might win all three, or two, or one.

The thing is, even if BNP wins all three, and gets a morale boost, there might still be a lot for the regime. If BNP were to win on the 28th, on the morning of the 29th, the Prime Minister will claim ‘see, fair election possible under us’, invite the mayors-elect to Ganabhaban and promise full co-operation. The editorials on the 30th will then be full of praise for Mrs Wajed’s statesmanship, and BNP’s pettiness and idiocy.

Of course, as things stand, the mayors and their councils have no power over anything substantial. In fact, by allowing these local government elections, the PM is following in the footsteps of the military regimes of HM Ershad or Ayub Khan, or the Raj going back a century — they too allowed elections of local bodies with limited powers to pacify restive subjects. As such, it’s easy to think about sitting out these elections.

Such cynicism would be wrong.

For one thing, just as was the case under the Raj or the generals, these elections provide an avenue for new politicians to emerge. Indeed, anyone who claims to be tired of the two netris or politics-as-usual must take these elections seriously. If not through elections, how else do they propose new leadership will emerge?

Dhaka North is particularly important. A directly elected mayor of the richest and most educated part of the country — one can think of far worse ways of nurturing new leadership. The mayor-elect of Dhaka North might have little power on paper. But he will have tremendous symbolic and moral authority, which may well provide seed capital for a bright political future.

Further, there really is a choice in Dhaka North. Annisul Huq, Zonayed Saki, Mahi B Chowdhury, Tabith Awal — each of them offer different things, and you should think carefully before exercising your right (if you can) on the 28th.

Take Annisul Huq, the Prime Minister’s choice. If you believe the PM is doing a helluva job, then clearly you should vote for Mr Huq. And by the same token, a vote for Mr Huq would mean this is what you really think.

If you fancy yourself as one of the left, if you like railing against ‘neoliberalism’, if you went to Shahbag and then soured on Awami League, then Mr Saki is your man. Now, my politics is decidedly not of the left. I think Marx was right about many things but was wrong about the most important matters, and I have a very dim view of non-Marxist populism. But this post is not a critique of the left. Relevant thing for us is that by joining the hustings, Mr Saki is signalling that he takes the hard work of politics seriously. That is to be commended. If you are serious about the left, then you should vote for him, not Mr Huq.

I am not really sure I see anything commendable in Mr Chowdhury. I understand he is media-savvy. He portrays himself as a face of the youth. I guess in Bangladesh a 46 year old can pass for young. But Mr Chowdhury is not a new face. He has been in politics for a decade and half. He has had plenty of chance to show his acumen. And he has delivered nought. Nought is also what he has achieved outside politics. A vote for him is a lazy choice, a thoughtless choice, symbolising nothing but the voter’s unwillingness to take things seriously. As it happens, I doubt Mr Chowdhury will get far. And just as well, for a good showing by Mr Chowdhury would mean worse for future for our politics than a resounding win for Mr Huq.

And that leaves us with Mr Awal. At 36, he would be considered young for politics anywhere in the world. He is a genuinely new face in politics. The politically apathetic might dismiss him as being a parachuted candidate with a silver spoon. Dismissing Tabith Awal out of such cynicism, however, would be a bad mistake. Mr Awal is no more a parachuted candidate than Mr Huq. He is far less a dynastic scion than Mr Chowdhury. And at least by one measure, he has shown greater commitment to people’s rights than Mr Saki — in late 2013, when the most fundamental of democratic rights, the right to choose one’s government, was being snatched, Mr Awal courted arrest. Indeed, by that measure, Tabith Awal has shown greater political courage than any of his opponents.

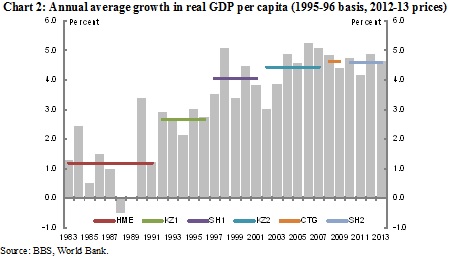

There is a lot of things wrong with BNP. But endorsing Mr Awal’s candidacy is not one of them. If you take your rights seriously, if you want the 6% growth and associated social development to continue, if you want to heal the fissure of Shahbag and Shapla Chattar, you must welcome men and women like Mr Awal into politics.

Tabith Awal may be the youngest candidate in Dhaka North, but a vote for him is the mature thing to do.

First Published at https://jrahman.wordpress.com/2015/04/25/something-for-everyone/#more-4090

Recent Comments